Scaling Kubernetes with Metal3: Simulating 1000 Clusters with Fake Ironic Agents

If you’ve ever tried scaling out Kubernetes clusters in a bare-metal environment, you’ll know that large-scale testing comes with serious challenges. Most of us don’t have access to enough physical servers—or even virtual machines—to simulate the kinds of large-scale environments we need for stress testing, especially when deploying hundreds or thousands of clusters.

That’s where this experiment comes in.

Using Metal3, we simulated a massive environment—provisioning 1000 single-node Kubernetes clusters—without any actual hardware. The trick? A combination of Fake Ironic Python Agents (IPA) and Fake Kubernetes API servers. These tools allowed us to run an entirely realistic Metal3 provisioning workflow while simulating thousands of nodes and clusters, all without needing a single real machine.

The motivation behind this was simple: to create a scalable testing environment that lets us validate Metal3’s performance, workflow, and reliability without needing an expensive hardware lab or virtual machine fleet. By simulating nodes and clusters, we could push the limits of Metal3’s provisioning process cost-effectively and time-efficiently.

In this post, I’ll explain exactly how it all works, from setting up multiple Ironic services to faking hardware nodes and clusters and sharing the lessons learned. Whether you’re a Metal3 user or just curious about how to test large-scale Kubernetes environments, it’ll surely be a good read. Let’s get started!

Prerequisites & Setup

Before diving into the fun stuff, let’s ensure we’re on the same page. You don’t need to be a Metal3 expert to follow along, but having a bit of background will help!

What You’ll Need to Know

Let’s start by ensuring you’re familiar with some essential tools and concepts that power Metal3 workflow. If you’re confident in your Metal3 skills, please feel free to skip this part.

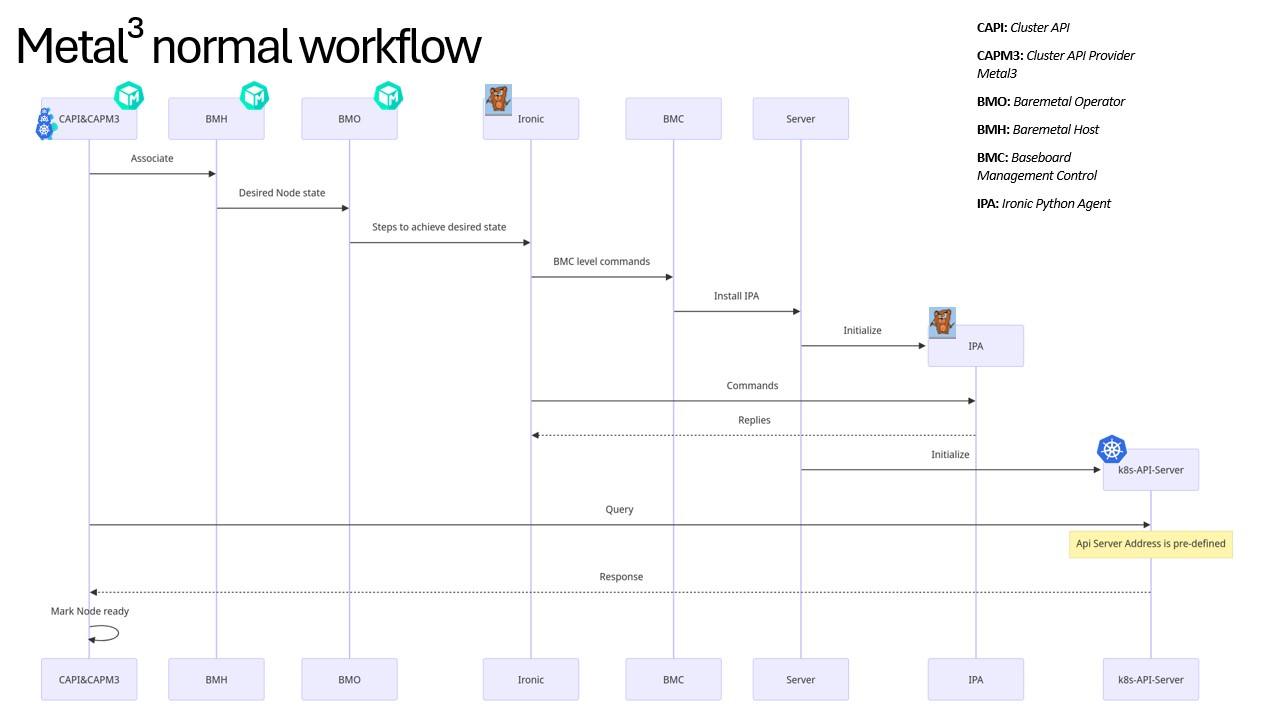

A typical Metal3 Workflow

The following diagram explains a typical Metal3 workflow. We will, then, go into details of every component.

Cluster API (CAPI)

CAPI is a project that simplifies the deployment and management of Kubernetes clusters. It provides a consistent way to create, update, and scale clusters through Kubernetes-native APIs. The magic of CAPI is that it abstracts away many of the underlying details so that you can manage clusters on different platforms (cloud, bare metal, etc.) in a unified way.

Cluster API Provider Metal3 (CAPM3)

CAPM3 extends CAPI to work specifically with Metal3 environments. It connects the dots between CAPI, BMO, and Ironic, allowing Kubernetes clusters to be deployed on bare-metal infrastructure. It handles tasks like provisioning new nodes, registering them with Kubernetes, and scaling clusters.

Bare Metal Operator (BMO)

BMO is a controller that runs inside a Kubernetes cluster and works alongside Ironic to manage bare-metal infrastructure. It automates the lifecycle of bare-metal hosts, managing things like registering new hosts, powering them on or off, and monitoring their status.

Bare Metal Host (BMH)

A BMH is the Kubernetes representation of a bare-metal node. It contains information about how to reach the node it represents, and BMO monitors its desired state closely. When BMO notices that a BMH object state is requested to change (either by a human user or CAPM3), it will decide what needs to be done and tell Ironic.

Ironic & Ironic Python Agent (IPA)

- Ironic is a bare-metal provisioning tool that handles tasks like booting servers, deploying bootable media (e.g., operating systems) to disk, and configuring hardware. Think of Ironic as the piece of software that manages actual physical servers. In a Metal3 workflow, Ironic receives orders from BMO and translates them into actionable steps. Ironic has multiple ways to interact with the machines, and one of them is the so-called “ agent-based direct deploy” method, which is commonly used by BMO. The agent mentioned is called Ironic Python Agent (IPA), which is a piece of software that runs on each bare-metal node and carries out Ironic’s instructions. It interacts with the hardware directly, like wiping disks, configuring networks, and handling boot processes.

In a typical Metal3 workflow, BMO reads the desired state of the node from the BMH object, translates the Kubernetes reconciling logic to concrete actions, and forwards them to Ironic, which, as part of the provisioning process, tells IPA the exact steps it needs to perform to get the nodes to desired states. During the first boot after node image installation, Kubernetes components will be installed on the nodes by cloud-init, and once the process succeeds, Ironic and IPA finish the provisioning process, and CAPI and CAPM3 will verify the health of the newly provisioned Kubernetes cluster(s).

The Experiment: Simulating 1000 Kubernetes Clusters

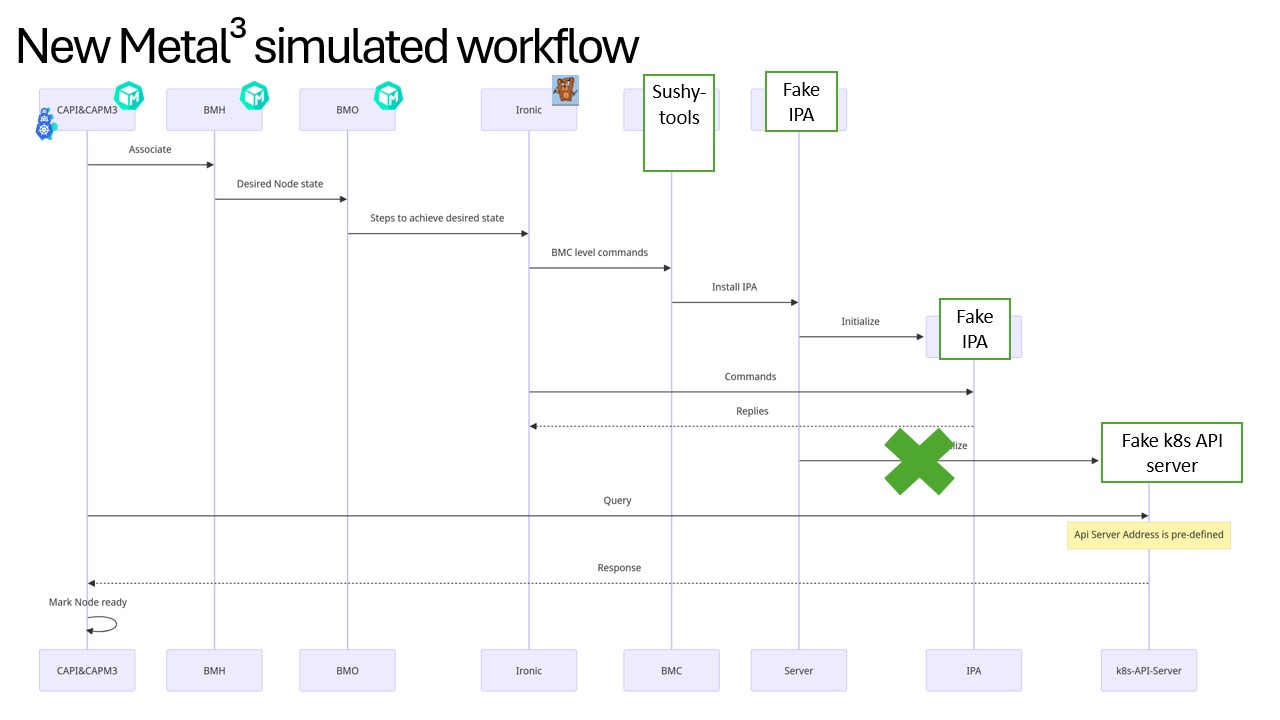

This experiment aimed to push Metal3 to simulate 1000 single-node Kubernetes clusters on fake hardware. Instead of provisioning real machines, we used Fake Ironic Python Agents (Fake IP) and Fake Kubernetes API Servers (FKAS) to simulate nodes and control planes, respectively. This setup allowed us to test a massive environment without the need for physical infrastructure.

Since our goal is to verify the Metal3 limit, our setup will let all the Metal3 components (except for IPA, which runs inside and will be scaled with the nodes) to keep working as they do in a typical workflow. In fact, none of the components should be aware that they are running with fake hardware.

Take the figure we had earlier as a base, here is the revised workflow with fake nodes.

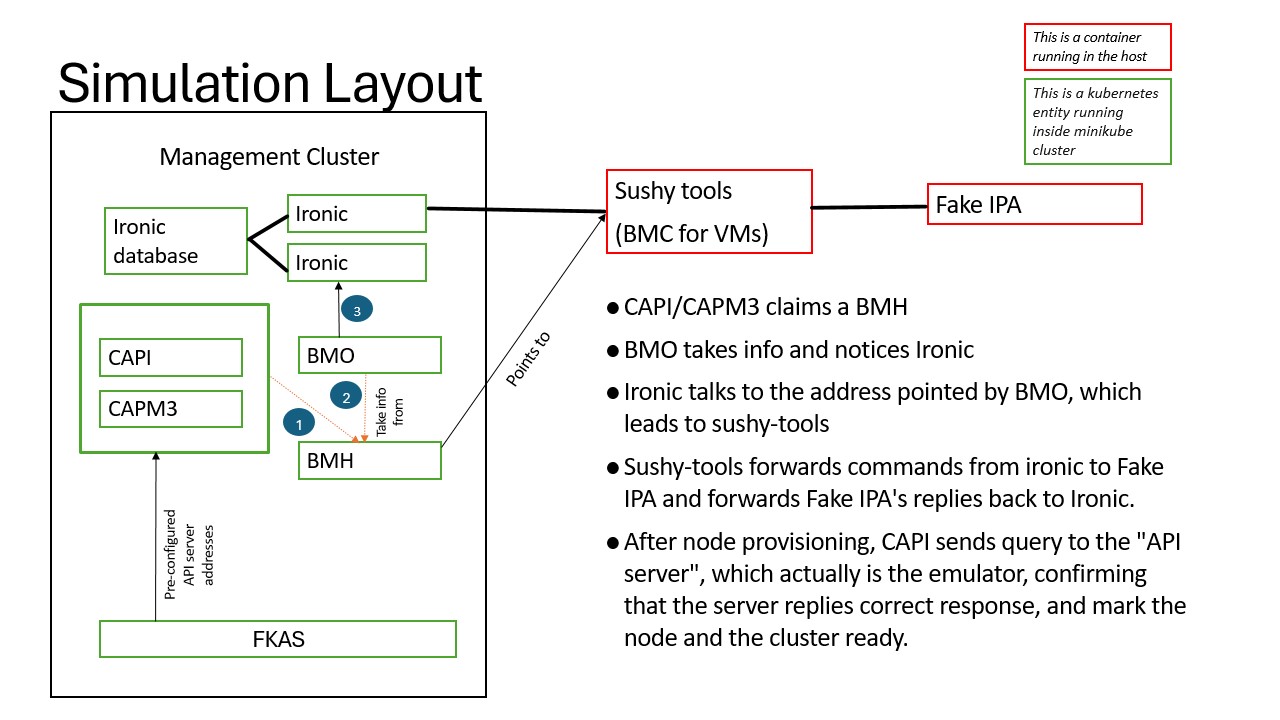

Step 1: Setting Up the environment

As you may have known, a typical Metal3 workflow requires several components: bootstrap Kubernetes cluster, possible external networks, bare-metal nodes, etc. As we are working on simulating the environment, we will start with a newly spawned Ubuntu VM, create a cluster with minikube, add networks with libvirt, and so on (If you’re familiar with Metal3’s dev-env, this step is similar to what script 01, 02 and a part of 03 do). We will not discuss this part, but you can find the related setup from this script if interested.

Note: If you intend to follow along, note that going to 1000 nodes requires a large environment and will take a long time. In our setup, we had a VM with 24 cores and 32GB of RAM, of which we assigned 14 cores and 20GB of RAM to the minikube VM, and the process took roughly 48 hours. If your environment is less powerful, consider reducing the nodes you want to provision. Something like 100 nodes will require minimal resources and time while still being impressive.

Step 2: Install BMO and Ironic

In Metal3’s typical workflow, we usually rely on Kustomize to install Ironic and BMO. Kustomize helps us define configurations for Kubernetes resources, making it easier to customize and deploy services. However, our current Kustomize overlay for Metal3 configures only a single Ironic instance. This setup works well for smaller environments, but it becomes a bottleneck when scaling up and handling thousands of nodes.

That’s where Ironic’s special mode comes into play. Ironic has the ability

to run multiple Ironic conductors while sharing the same database. The best

part? Workload balancing between conductors happens automatically, which means

that no matter which Ironic conductor receives a request, the load is evenly

distributed across all conductors, ensuring efficient provisioning. Achieving

this requires separating ironic conductor from the database, which allows us

to scale up the conductor part. Each conductor will have its own

PROVISIONING_IP, hence the need to have a specialized configMap.

We used Helm for this purpose. In our Helm chart, the

Ironic conductor container and HTTP server (httpd) container are

separated into a new pod, and the rest of the ironic package (mostly

MariaDB-ironic database) stays in another pod. A list of PROVISIONING_IPs is

provided by the chart’s values.yaml, and for each IP, an ironic conductor

pod is created, along with a config map whose values are rendered with the IP’s

value. This way, we can dynamically scale up/down ironic (or, more specifically,

ironic conductors) by simply adding/removing ips.

Another piece of information that we need to keep in mind is the ipa-downloader container. In our current metal3-dev-env, the IPA-downloader container runs as an init Container for ironic, and its job is to download the IPA image to a Persistent Volume. This image contains the Ironic Python Agent, and it is assumed to exist by Ironic. For the multiple-conductor scenario, running the same init-container for all the conductors, at the same time, could be slow and/or fail due to network issue. To make it work, we made a small “hack” in the chart: the ipa image will exist in a specific location inside the minikube host, and all the conductor pods will mount to that same location. In production, a more throughout solution might be to keep the IPA-downloader as an init-container, but points the image to the local image server, which we set up in the previous step.

BMO, on the other hand, still works well with kustomize, as we do not need to scale it. As with typical metal3 workflow, BMO and Ironic must share some authentication to work with TLS.

You can check out the full Ironic helm chart here.

Step 3: Creating Fake Nodes with Fake Ironic Python Agents

As we mentioned at the beginning, instead of using real hardware, we will use a new tool called Fake Ironic Python Agent, or Fake IPA to simulate the nodes.

Setting up Fake IPA is relatively straightforward, as Fake IPA runs as containers on the host machine, but first, we need to create the list of “nodes” that we will use (Fake IPA requires to have that list ready when it starts). A “node” typically looks like this

{

"uuid": $uuid,

"name": $node_name,

"power_state": "Off",

"external_notifier": "True",

"nics": [

{"mac": $macaddr, "ip": "192.168.0.100"}

],

}

All of the variables (uuid, node_name, macaddress) can be dynamically

generated in any way you want (check this

script

out if you need an idea). Still, we must store this information to generate the

BMH objects that match those “nodes.” The ip is, on the other hand, not

essential. It could be anything.

We must also start up the sushy-tools container in this step. It is a tool that simulates the Baseboard Management Controller for non-bare-metal hardware, and we have been using it extensively inside Metal3 dev-env and CI to control and provision VMs as if they are bare-metal nodes. In a bare-metal setup, Ironic will ask the BMC to install IPA on the node, and in our setup, sushy-tools will get the same request, but it will simply fake the installation and, in the end, forward Ironic traffic to the Fake IPA container.

Another piece of information we will need is the cert that Ironic will use in its communication with IPA. IPA is supposed to get it from Ironic, but as Fake IPA cannot do that (at least not yet), we must get the cert and provide it in Fake IPA config.

mkdir cert

kubectl get secret -n baremetal-operator-system ironic-cert -o json \

-o=jsonpath="{.data.ca\.crt}" | base64 -d >cert/ironic-ca.crt

Also note that one set of sushy-tools and Fake IPA containers won’t be enough to provision 1000 nodes. Just like Ironic, they need to be scaled up extensively (about 20-30 pairs will be sufficient for 1000 nodes), but fortunately, the scaling is straightforward: We just need to give them different ports. Both of these components also require a Python-based config file. For convenience, in this setup, we create a big file and provide it to both of them, using the following shell script:

for i in $(seq 1 "$N_SUSHY"); do

container_conf_dir="$SUSHY_CONF_DIR/sushy-$i"

# Use round-robin to choose fake-ipa and sushy-tools containers for the node

fake_ipa_port=$((9901 + (($i % ${N_FAKE_IPA:-1}))))

sushy_tools_port=$((8000 + i))

ports+=(${sushy_tools_port})

# This is only so that we have the list of the needed ports for other

# purposes, like configuring the firewalls.

ports+=(${fake_ipa_port})

mkdir -p "${container_conf_dir}"

# Generate the htpasswd file, which is required by sushy-tools

cat <<'EOF' >"${container_conf_dir}"/htpasswd

admin:$2b$12$/dVOBNatORwKpF.ss99KB.vESjfyONOxyH.UgRwNyZi1Xs/W2pGVS

EOF

# Set configuration options

cat <<EOF >"${container_conf_dir}"/conf.py

import collections

SUSHY_EMULATOR_LIBVIRT_URI = "${LIBVIRT_URI}"

SUSHY_EMULATOR_IGNORE_BOOT_DEVICE = False

SUSHY_EMULATOR_VMEDIA_VERIFY_SSL = False

SUSHY_EMULATOR_AUTH_FILE = "/root/sushy/htpasswd"

SUSHY_EMULATOR_FAKE_DRIVER = True

SUSHY_EMULATOR_LISTEN_PORT = "${sushy_tools_port}"

EXTERNAL_NOTIFICATION_URL = "http://${ADVERTISE_HOST}:${fake_ipa_port}"

FAKE_IPA_API_URL = "${API_URL}"

FAKE_IPA_URL = "http://${ADVERTISE_HOST}:${fake_ipa_port}"

FAKE_IPA_INSPECTION_CALLBACK_URL = "${CALLBACK_URL}"

FAKE_IPA_ADVERTISE_ADDRESS_IP = "${ADVERTISE_HOST}"

FAKE_IPA_ADVERTISE_ADDRESS_PORT = "${fake_ipa_port}"

FAKE_IPA_CAFILE = "/root/cert/ironic-ca.crt"

SUSHY_FAKE_IPA_LISTEN_IP = "${ADVERTISE_HOST}"

SUSHY_FAKE_IPA_LISTEN_PORT = "${fake_ipa_port}"

SUSHY_EMULATOR_FAKE_IPA = True

SUSHY_EMULATOR_FAKE_SYSTEMS = $(cat nodes.json)

EOF

# Start sushy-tools

docker run -d --net host --name "sushy-tools-${i}" \

-v "${container_conf_dir}":/root/sushy \

"${SUSHY_TOOLS_IMAGE}"

# Start fake-ipa

docker run \

-d --net host --name fake-ipa-${i} \

-v "${container_conf_dir}":/app \

-v "$(realpath cert)":/root/cert \

"${FAKEIPA_IMAGE}"

done

In this setup, we made it so that all the sushy-tools containers will listen on the port range running from 8001, 8002,…, while the Fake IPA containers have ports 9001, 9002,…

Step 4: Add the BMH objects

Now that we have sushy-tools and Fake IPA containers running, we can already generate the manifest for BMH objects, and apply them to the cluster. A BMH object will look like this

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: name-bmc-secret

labels:

environment.metal3.io: baremetal

type: Opaque

data:

username: YWRtaW4=

password: cGFzc3dvcmQ=

---

apiVersion: metal3.io/v1alpha1

kind: BareMetalHost

metadata:

name: name

spec:

online: true

bmc:

address: redfish+http://192.168.222.1:{port}/redfish/v1/Systems/{uuid}

credentialsName: name-bmc-secret

bootMACAddress: random_mac

bootMode: legacy

In this manifest:

nameis the node name we generated in the previous step.uuidis the random uuid we generated for the same node.random_macis a random mac address for the boot. It’s NOT the same as the NIC mac address we generated for the node.portis the listening port on one of the sushy-tools containers we created in the previous step. Since every sushy-tools and Fake IPA container has information about ALL the nodes, we can decide what container to locate the “node”. In general, it’s a good idea to spread them out, so all containers are loaded equally.

We can now run kubectl apply -f on one (or all of) the BMH manifests. What you

expect to see is that a BMH object is created, and its state will change from

registering to available after a while. It means ironic acknowledged

that the node is valid, in good state and ready to be provisioned.

Step 5: Deploy the fake nodes to kubernetes clusters

Before provisioning our clusters, let’s init the process, so that we have CAPI and CAPM3 installed

clusterctl init --infrastructure=metal3

After a while, we should see that CAPI, CAPM3, and IPAM pods become available.

In a standard Metal3 workflow, after having the BMH objects in an available

state, we can provision new Kubernetes clusters with clusterctl. However, with

fake nodes, things get a tiny bit more complex. At the end of the provisioning

process, Cluster API expects that there is a new kubernetes API server

created for the new cluster, from which it will check if all nodes are up, all

the control planes have apiserver, etcd, etc. pods up and running, and so

on. It is where the Fake Kubernetes API Server

(FKAS)

comes in.

As the FKAS README linked above already described how it works, we won’t go

into details. We simply need to send FKAS a register POST request (with

the new cluster’s namespace and cluster name), and it will give us an IP and a

port, which we can plug into our cluster template and then run clusterctl

generate cluster.

Under the hood, FKAS generates unique API servers for different clusters. Each of the fake API servers does the following jobs:

- Mimicking API Calls: The Fake Kubernetes API server was set up to respond to the essential Kubernetes API calls made during provisioning.

- Node Registration: When CAPM3 registered nodes, the Fake API server returned success responses, making Metal3 believe the nodes had joined a real Kubernetes cluster.

- Cluster Health and Status: The Fake API responded with “healthy” statuses, allowing CAPI/CAPM3 to continue its workflow without interruption.

- Node Creation and Deletion: When CAPI queried for node status or attempted to add/remove nodes, the Fake API server responded realistically, ensuring the provisioning process continued smoothly.

- Pretending to Host Kubelet: The Fake API server also simulated kubelet responses, which allowed CAPI/CAPM3 to interact with the fake clusters as though they were managing actual nodes.

Note that in this experiment, we provisioned every one of the 1000 fake nodes to

a single-node cluster, but it’s possible to increase the number of control

planes and worker nodes by changing the --control-plane-machine-count and

worker-machine-count parameters in the clusterctl generate cluster command.

However, you will need to ensure that all clusters’ total nodes do not exceed

the number of BMHs.

As a glance, the whole simulation looks like this:

It will likely take some time, but once the BMHs are all provisioned, we should be able to verify that all, or at least, most of the clusters are in good shape:

# This will list the clusters.

kubectl get clusters -A

# This will determine the clusters' readiness.

kubectl get kcp -A

- For each cluster, it’s also a good idea to perform a clusterctl check.

Accessing the fake cluster

A rather interesting (but not essential for our goal) check we can perform on the fake clusters is to try accessing them. Let’s start with fetching a cluster’s kubeconfig:

clusterctl -n <cluster-namespace> get kubeconfig <cluster-name> > kubeconfig-<cluster-name>.yaml

As usual, clusterctl will generate a kubeconfig file, but we cannot use it

just yet. Recall that we generated the API endpoint using FKAS; the address we

have now will be a combination of a port with FKAS’s IP address, which isn’t

accessible from outside the cluster. What we should do now is:

- Edit the

kubeconfig-<cluster-name>.yamlso that the endpoint is in the formlocalhost:<port>. - Port-forward the FKAS Pod to the same port the kubeconfig has shown.

And voila, now we can access the fake cluster with kubectl --kubeconfig

kubeconfig-<cluster-name>.yaml. You can inspect its state and check the

resources (nodes, pods, etc.), but we won’t be able to run any workload on it as

it’s fake.

Results

In this post, we have demonstrated how it is possible to “generate” bare-metal-based Kubernetes clusters from thin air (or rather, a bunch of nodes that do not exist). Of course, these “clusters” are not very useful. Still, successfully provisioning them without letting any of our main components (CAPI, CAPM3, BMO, and Ironic) know they are working with fake hardware proves that Metal3 is capable of handling a heavy workload and provision multiple nodes/clusters.

If interested, you could also check (and try out) the experiment by yourself here.